Have you ever wondered how a watch is made or who makes the components? For me, to be frank, such questions never really crossed my mind – at least for many years. As long as I liked the appearance of a watch, it did what I wanted and I could afford it, job done! It was only when I began collecting more seriously and then started to do some writing (when I had to delve more deeply), that a certain curiosity ensued. Ongoing reading of the usual specialist magazines (hard copy and web) and going to events further enhanced my education. All that said, nothing, repeat nothing, beats actually going on a trip and seeing first hand what goes on behind the scenes. I was luckily afforded the opportunity to be embedded within such a trip in May, with resurrected brand Czapek. What follows is kind of a travelogue of what occurred. It may not be as technical or eloquent as other folk’s reports, but hey, journalism is not my real profession!

So, what was the Genesis of all this? Well, after having ordered a Czapek Faubourg de Cracovie L’Heure Bleu chronograph last November, CEO Xavier de Roquemaurel said that I should come over to Geneva and collect it. I briefly considered, but then parked the idea as it was all a bit too rushed and near Xmas. In addition, just when the watch was ready (in late December) Czapek were busy getting their new Geneva boutique ready for Xmas/New Year. In the end the piece was sent over to London where I collected it in mid-January.

I loved the watch. It was all that I could have wanted of it’s type – right size and functions, unique design, quality components, interesting story, and, well, pretty rare being one of eighteen (in fact unique, as mine is the only one to have an entirely red second hand!). The latter aspect was important to me. Why? Well, yes, Omega Speedmasters and Rolex Daytonas et al are great chronograph watches (I have an example of the former) and reasonably affordable (well some are), but production has been huge, so walk into a room full of enthusiasts and, well, you may just appear a little lemming-like. At the other end of the scale, yes, I would love the rarity of say an older Patek chronograph, but at a price probably upwards of £100k it is unrealistic. I liken it all to owning a BMW thirty years ago – which I was fortunate to do. Then, there were not too many around, and having one was a big deal as it reflected not only your business achievements, but also your discernment of understated quality. Now – and no disrespect to that maker, they are pretty common and every Tom, Dick and Harry has one. In part we can blame cheap and liberal finance for that! In the end I defected to SAAB some 18 years ago in an effort to obtain under the radar exclusivity with style, comfort and quality. I had three 95 estates in a row and all were great, but the last one, an Aero, was a real cracker. I loved them, but it all ended in tragedy when they went bust so I had to consider alternatives. However, not being one to cut my nose to spite my face, I reverted back to the Bayerische brand and 5 Series Tourers. My current 530d is probably the best car I have ever had, period, and is also usually rated best in class. So, good quality, expensive (but not madly so), and this model is not too common! The point of all this is that I prefer to go a bit off-piste with things, trying to get the best at my budget and if possible, lower production. The Czapek fitted this strategy nicely.

Anyway, I liked the watch so much I wanted to write about it. Due to some twists of fate I was afforded the opportunity to do so for The Watchmakers Club website. So, I approached Czapek and they were were very free in providing information and patiently answered my sometimes odd questions. This yielded more interesting facts about some of the atelier manufactures that they use. The article came to fruition in March and was apparently (to my surprise) well received, and Xavier in particular was delighted as the piece was generally flattering. Well, I was hardly going to do otherwise on a watch that I had recently bought! He then again raised the idea coming out to see them. This time I did now feel more ready so we pencilled in a slot in May (this was in fact timely as the Watchlogic site was due to ignite just before then, with one of the first articles penned by The Writer – me, being a slightly truncated version of The Watchmakers Club piece on my Czapek chronograph). At that time I only knew that I would be based in Neuchatel – in and around where much of Switzerland’s actual watch making and component manufacturing occurs. Xavier also lives there, plus, Czapek’s HQ/workshop is in nearby Le Locle. Places to visit would include their movement, hand and case makers. A few “proper” journalists would also join in the fun too!

The departure day arrived. I had in fact an interesting flight out as the chap who I was sitting next to worked for a US private jet servicing company. He was on his way to a convention at Geneva airport in order to drum up more business. It turned out that he was quite interested in watches and showed me his Breitling – possibly a Chronomat but in truth I cannot actually recall. The watch was unusual as it has his company’s logo on the dial and on the reverse their name plus a note that it was one of a limited edition of 50. He explained that occasionally his firm would order these – principally as client gifts. I asked him how much it cost to service a small jet – like a Citation. Much depended on age and air miles done of course, but seemingly well into six figures. So, giving out occasional watch gifts is small beer in the overall scheme of things!

At Geneva airport I boarded the free train into the city proper. Xavier’s head of communication, Valeria, had already kindly e-mailed me a map of the city and this revealed that their boutique (my first port of call) was about maybe only a 15 minute walk. This was a pleasant experience as it took me over the river and in nice sunshine.

At the boutique I met Pierre, the manager, and also Czapek’s digital guru. He was just meeting some corporate gift suppliers doing a pitch, but asked me to sit in and throw my thoughts in too! After this concluded I spent a further hour or so chatting about their watches and taking photos of some interesting pieces – such as the limited edition manual winding Place Vendome Tourbillon range. In this case one in titanium called “Ombres” (or Shadows), and another in rose gold, called “Lumiere”. Regarding the latter I was most fortunate as they had a beautifully engraved version by Michelle Roten. As usual, tourbillon watches command a pretty hefty premium over their more humble powered brethren. The Ombres weighs in at some CHF 88,000 and the super-special Lumiere up from it’s base CHF 95,000 to CHF 125,000. There was also the Quai Des Bergues special boutique edition – Midnight in Geneva, which has a wonderful aventurine glass bombe dial in deep blue with tiny bright flecks to represent stars. Also, some new dial types for the popular Faubourg De Cracovie chronograph were there – see my article on this specific model on the site.

After this I decided to head to Neuchatel and my hotel, so walked back to the station. After having got my ticket – with some assistance from another passenger (I am confused by ticket machines anyway let alone in a another language – notwithstanding the fact that I can speak/read some French!) the journey was uneventful but efficient, taking some 1hr 20.

Before I set off, Xavier had texted me to say that he was now at home and would meet me at the station. This was kind and in the event we walked the short distance to his home where I met his charming wife Marie-Alix and children – well some of them as not all 5 were in! I presented Xavier with a bottle of gin (distilled locally to where I live) and some nice cigars – all of which we promptly sampled! After a late night snack we wandered down to my hotel (Touring Au Lac) which was in a good position being almost on the lake front and next to a small harbour. After having checked in we had a brief stroll along the lakeside, where we found a peculiar monument. As it was dark I vowed to return the next day to examine more thoroughly, and so did. A plaque indicated that it was a “meteorological column” and “measuring station”, erected in 1854 by the local Natural Science Society. On each side there was an instrument set into the stonework. As far as I can recall, these included; a clock, barometer, altimeter, and hygrometer and finally a weather vane atop.

The hotel was fairly basic – no restaurant/bar etc, but clean, well run and reasonably priced. There was a decent breakfast room with a more than adequate buffet. I had by this time discovered that the journalists and Valeria were also booked in for the following night – not only coincidental but also reassuring! I do not really sleep well in hotels – they are invariably too hot with suspect beds, but in the event I had a decent night.

I was ready and waiting at eleven when Xavier arrived in his people carrier (remember, 5 children). We set off for a restaurant called Les Six Communes in Motiers, some half an hour west of Neuchatel (so heading more deeply into the watch-making area) and we would all meet up there.The day was again sunny and the scenery was picture postcard. We stopped briefly to admire the view, and then noticed a small cemetery nestled at the bottom of a field. I commented that I would not mind in the least if that was my final resting place! Xavier agreed and walked down to inspect. On his return he had a phone call from Valeria to say that she had arrived and they were waiting for us!

We duly arrived at the restaurant and this was picturesque, old and very quaint. Introductions were quickly made. Our party comprised of six souls – myself, Xavier, Valeria, Ash (from Europa Star) Gerard (from Fratello), and Lukasz (from CH24.PL). We had a very nice lunch and frankly had to be prised away as we were all having a nice time chatting! Kari Voutilainen was also dining there – his manufacture being nearby, so, Xavier said hello. Small world! It was then a short drive to Fleurier and our first factory visit.

Waeber HMS, who manufacture hands, are based in an ultra modern black-glassed rectangular factory just into Fleurier. They are not a terribly old business, having started in 2001. We were met by the founder’s son, Laurent Waeber.

We initially convened in a meeting room where Laurent gave us a quick overview of the company, the processes, and the types of hands and finishes they produce. We then set off for the factory tour – having been advised that whilst we were able to take photos he would tell us when we could. Like other factories in the region, they supply a number of well-known watch brands but this needs to remain confidential!

What struck me immediately was the clinical nature of the facility. There were practically airlocks between departments, with air conditioning on to remove dust particles. Everything was supremely neat and tidy. All staff wore white coats and sat very quietly whilst methodically working. We too had to don white disposable boiler suits and plastic shoe coverings.

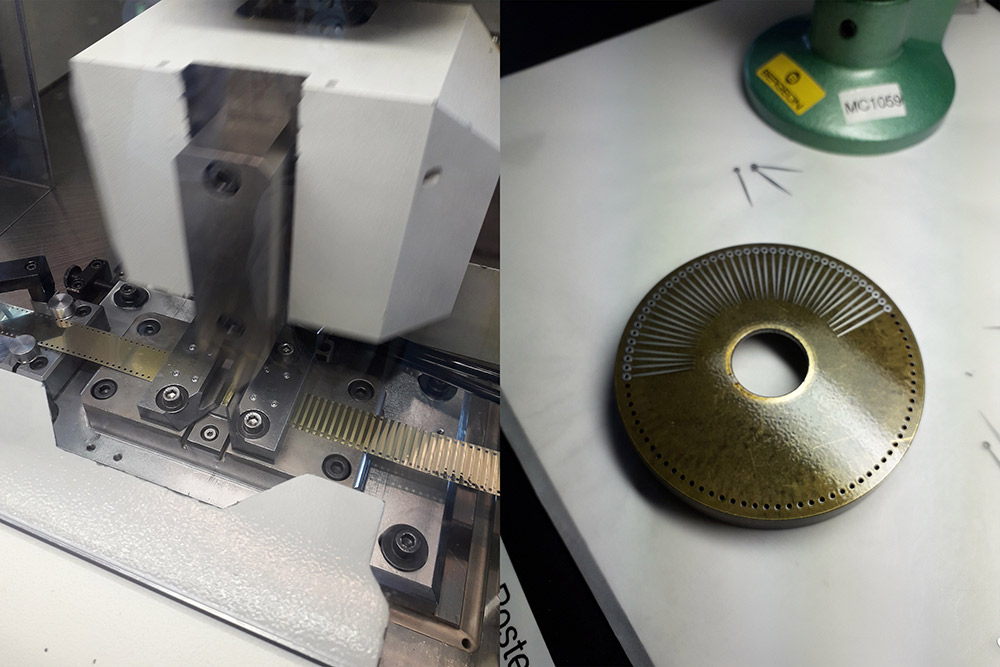

I could try and describe each department and process in minutiae, but that would get boring, and frankly I cannot actually recall in detail everything we saw as there was so much! Suffice to say that we moved from seeing the raw material – essentially reels of thin flat metal (steel or gold) going through machines that punched out the hands, to another machine that made holes in one end. Other machines would then rhodium plate or “blue” the hands by heating – the length of time would determine the ultimate colour. Some hands would be highly polished with maybe 50 being glued onto a round disc first. How, I asked, did one then remove the hands? Simple – the disc was immersed in a hot bath, thus softening the glue so that the hands simply floated off! Another machine made the tiny tube columns that the hands would then be fitted onto. The last department dealt with the painting of hands (we saw a lady hand spray painting some with red detailing), and lume application. The latter was interesting as this is essentially was a paste which filled the gap of a “skeleton” hand, but the consistency was such that it did not fall through. It was then heat treated to set, then hand finished to achieve perfection.

The tour was then at an end. Needless to say I had a new appreciation of just what goes into the initially thought simple task of making watch hands. Yes, there is a fair bit of automation but also an equal amount of human intervention and undoubted skill. Also, the many hand shapes (spade, dauphin, Breguet, dagger, sword, Mercedes, leaf, syringe and baton – phew!) and finishes were far more than one would imagine. Although not an “ancient ” business Waeber are pretty big in their field, apparently making some 2.2 million items per year, and for some well-known high end brands. Anyway, it was now time to move on.

Vaucher Manufacture Fleurier was next on the list. We were by this time rather behind schedule so it was fortunate they were also in Fleurier. The facility was again a fairly large modern building, seemingly just having being “dropped” into a beautiful location!

Vaucher make various movements – automatic and manual. The business roots are interesting and go back to Peter Parmigiani who started effectively a restoration business back in 1975. He then set up Parmiagiani Mesure et Art du Temps (PMAT) in 1990. The Sandoz family became a shareholder in 1995 and the first Parmigiani watches launched the next year. Some other specific component manufacturers were acquired in 2001 in order to secure supply. In 2003 PMAT was split in two – with Vaucher being the pure movement side, and Parmiagiani a stand-alone brand. In 2006 Hermes became a 25% shareholder too in VMF. In 2009 VMF moved to a brand new facility and that is where we stand today.

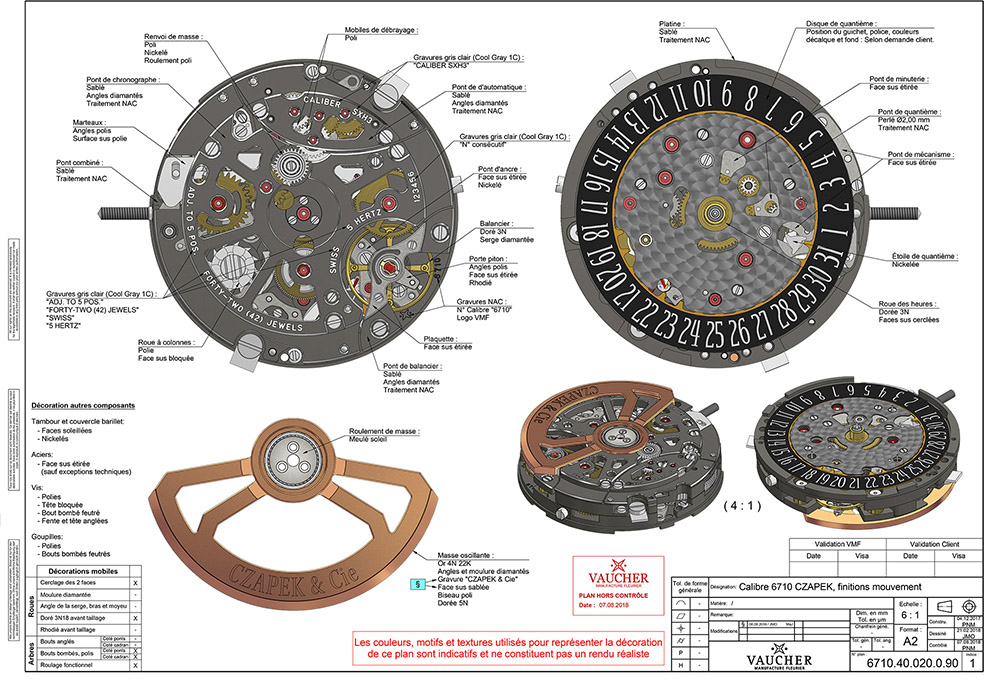

So, VMF naturally mainly make for Parmigiani and Hermes. They do the assembly and some manufacturing on-site, but also with assistance from the other members in the group such as: Elwin (micro components – like screws), Les Artisans Boitiers (cases) and Quadrance et Habillage (dials). However, in 2018, and for the first time, Vaucher agreed to supply Czapek with their fairly new integrated chronograph movement for the Faubourg de Cracovie. This has been modified in various ways to meet Czapek’s specific requirements , so is therefore unique, and from all accounts is one of the best movements of it’s type. In the Czapek iteration it is known as calibre SXH3.

As before, we had to don overalls and later on shoe covers too. Benoit, who is a watch maker and heads watch projects, led the tour and was most instructive and spoke very good English. He initially showed us a “history” chart on the wall in the foyer hall which showed the most notable aspects to date. Clearly most of these revolved around Peter Parmigiani, his initial watch/clock restoration business, then later his own watches and movements, and then other investors and specialist partner manufactures.

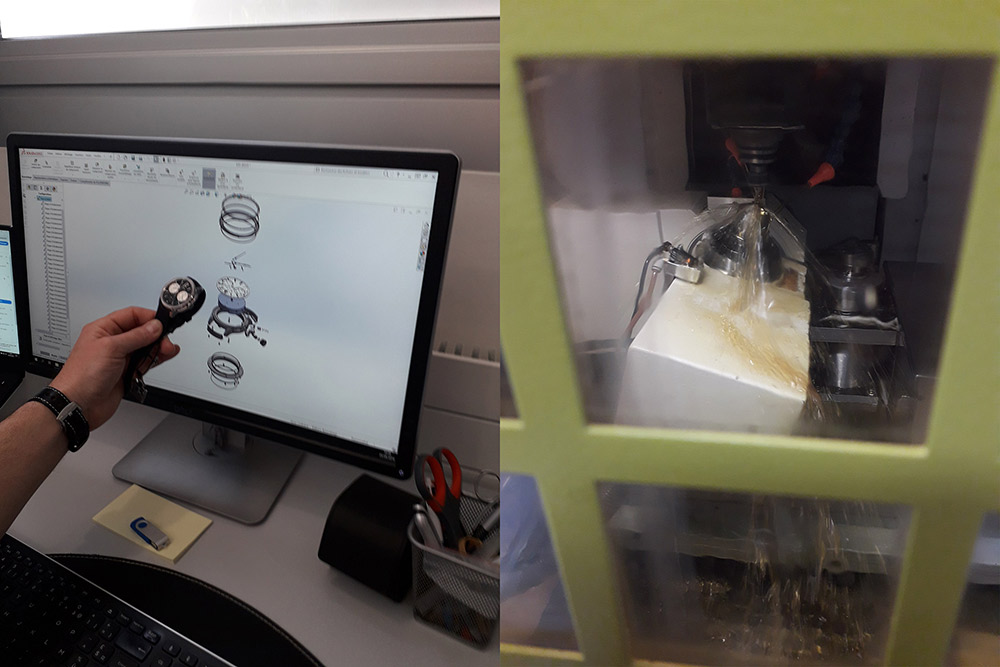

We then went into the design department, where much is now done of course using CAD (computer aided design), with on-screen watches and movements turning this way and that, and then exploding and imploding! I was wearing my chronograph so this came off to be compared with the computer design of the specific Czapek movement. It was most interesting to see what my movement looked like in pieces!

We then moved on to see various machines that essentially make metal parts – so CNC (computer numerical control) mills, lathes, lasers and so on. As time was passing we then went into the final assembly department. This had rows of high table and stools – which in part reminded me of the old physics labs at school. One main difference – aside from modern equipment, was the view of stunning scenery through large plate glass windows – lush green fields, cows and snow topped hills in the background. Working nirvana really! Anyway, we then met two watch makers who actually assemble the Czapek movements and so were able to view examples close up. Again, the attention to orderliness, discipline and cleanliness was all-pervading. Lastly, we then saw the automated CLA Chronometre machine that Vaucher use to test the accuracy of all the movements they make, and this can hold and test numerous movements in one go which was impressive. This is all in advance of the movements being sent for independent evaluation to, say, COSC, if the brand so requests. It was all most impressive. This tour was then at an end.

By this time the schedule had been somewhat blown apart so we headed back to Neuchatel, but first via Czapek’s workshop in Le Locle to pick up some watches so the journalists could all wear for the time being. Ash had alas had to say goodbye and return to Geneva as she had an important meeting early the next morning. So, back to the hotel for a quick spruce up and we then met up and headed out for some aperitifs at the stunning roof top restaurant/bar of the Beaulac Hotel, right on the lake shore. The sun was still out but just starting to set and we had a very pleasant time. Xavier and myself lit up cigars and we all posed for a group picture showing off our watches too. We then made our way to a nice restaurant in town, Brasserie Le Jura, and had a lovely meal. English was no problem as the owner, Ellen, came from Wigan in Lancashire!! After that we called it a day and headed off to bed.

The next morning we were all up reasonably early to be ready by 8am as our first visit was to Metalem in Chezard-Saint-Martin, and they are a guillochage (engravers). This was all a bit different in that their building was a pretty old house down a residential lane in the smallish town. We were met by Yannick and initially we sat in a small boardroom, where coffee was provided and examples of the different dial engravings were passed around. Yannick’s English was, well, limited, so the Czapek team translated. We then went into, I suppose, what I would call the engraving room, which had three rows of some six turning lathes with some being of the rose engine type. These specifically produce geometric and concentric patterns – like a rose. Some machines seemed fairly new but others not so. It is interesting to note that the first such machine was probably invented in the 1700s by a French engineer called Guillot. Before that, engraving was entirely done by hand which makes some of the earlier examples of dial and case decoration truly remarkable.

In very simple terms, the machine works like this; the blank dial is affixed to the end of a metal cylinder – a bit like a drill chuck. Behind the cylinder is a rosette cam (or cams) which has wavy edges – hence the rose monika. All this is connected via a pulley cable to a hand wheel that the engraver can turn (with their left hand) thus revolving the dial. The cylinder then moves slightly as per the the rosette type used – a different one required for each design. This is I suppose a simple (or not) form of programming. In front of the dial, and on the end of a sliding platform, is the engraving cutter (blade). With their right hand, the engraver pushes the platform gently forward so that the blade makes contact with the dial. The dial is then turned and the blade bites into the metal and a curved channel is made – or a wavy one, or whatever you need! At the top of the sweep, the blade is pulled back and the dial swung back ready for a new channel to be made. Before this however, the blade has of course to move to a slightly different position to make another grove and this is achieved via a small lever on the platform, which when activated clicks so you know the cutter has moved. The process is repeated. All the time the engraver is peering intently through some powerful bi-lenses.

This sounds all a bit easy doesn’t it? Not so!. The two aspects of real expertise are, firstly, the training and experience of the engraver who, when seen in action, just turns, pushes, clicks, turns, pushes, clicks all pretty quickly. The eye-to-hand co-ordination skill is very high, plus, applying just the right pressure to obtain the correct groove depth is critical. Secondly, translating the desired initial dial design into reality via the rosettes. This sometimes is by trial and error although more standard patterns are known and straightforward. All this though has to be “programmed” into the machine via the rosette so that along with the “click” the desired pattern emerges. To some extent the pure graphic side of the process is not unlike the Spirograph plastic toy I had in the late Sixties, where you could make some fantastic floral like patterns by using the eccentric nature of combining different sized toothed wheels. That though, was by comparison, very simple as I discovered!

We all then had the opportunity to have a go. To actually make an engraved arc was not so difficult but that’s where it all ended, and not well! My effort did not start and end in the right place and the depth was, well, like a seabed contour. Also, turning the wheel the wrong way was a handicap. There was laughter, but I maintained that with some more training I could do it as I have patience and am good with my hands. More laughter and a suggestion that when I retire I could have a new career. I said be careful what you wish for, as dependent on Brexit, I might just come knocking. More laughter. The tour ended and we were allowed to take our dials as souvenirs!

The next stop was AB Product in La Chaux-de-Fonds. The owners Aurelien Bouchet and Maxime Oudot met us and we sat down for an overview of the business. They mainly make watch components – largely cases, but also hands, crowns, buckles and screws. Again, for a fair variety of brands – mainly higher end but lowish volume. They also undertake other work including making jewellery components.

We then were taken around the facility, starting with the design suite. Here the initial work is done, as usual via CAD. Once that has been agreed, the item is then made in plastic by 3D printing and then in bronze.

We then went into the production area which was filled with various CNC machining, milling and laser cutters all busy converting billet stainless steel blocks into intricate watch cases – all automated which was fascinating to watch. At this point I was kindly offered a gift of a bronze case sample of my watch model. It was intriguing to see the naked shell with all its intricacies – including the holes drilled to accept the winder and pushers.

We then went into a room that checked metal components using, I think, a spectrometer, to ensure that there were no internal defects. Finally the sandblasting and polishing rooms. My bronze case was offered up to show how they sandblast the case recesses. Again, it was all very interesting. That concluded the tour.

Our final factory visit – a last minute arrangement, was to rubber strap maker Valience just up the road. Their CEO, Thierry, took us around the facility. This was quite brief as Xavier was just collecting some straps, but also as the actual manufacturing process was relatively straightforward. The rubber went in one end of the machine, was shaped, stamped and emerged with an embossed pattern on both sides. In this case it was a replica of the guilloche on the chronograph dial – smaller on the outside and larger inside. Pretty neat. Workers then hand finished the straps by expertly trimming and “filing” any rough edges. Xavier in fact kindly gave me a blue strap later on for my watch.

Our last official activity was a nice lunch at the Hotel de Ville restaurant in Chaux-de-Fonds. In homage to Czapek, we all took our watches off and made a display on the table.

That concluded the formal side of the trip. We went back to the Czapek atelier in Le Locle to meet properly the watchmakers and other staff and to see some new dial colours. Oh, and the loaned out watches to be returned! We then parted company – Valeria taking Gerard and Lukasz back to Geneva airport and I returned to Neuchatel with Xavier.

A final visit just with Xavier occurred the next day back in Geneva. This was leather watch strap maker Atelier du Bracelet. They kindly put another hole in my chronograph strap in order to really get the fit just right. I did in fact call back later in the day to meet Fabien to discuss the possibility of making a bespoke lizard strap for my vintage Vacheron.

Conclusions

I first mentioned the matter of outsourcing components in the The Watchmakers Club review of my L’Heure Bleu. Here, I acknowledged that this was the case with Czapek. Let’s be frank. If you are a relatively new brand is it all but impossible to make everything in-house unless one has not only unlimited funds but also the required skilled staff and facilities. Instead, one has to design the watch and then involve favoured (and willing) collaborators. Is this somehow a sub-standard route? Not so! One thing that the trip did reveal to me is that the factories I saw worked at a very high level of skill, discipline and dare I say cleanliness, resulting in exceptional quality production. All of this does not come cheap of course. Additionally, as mentioned earlier, such facilities make items for well-known brands at the pinnacle of haute horlogerie so let us not indulge in hypocrisy! I suppose the only obvious potential negative could be a control issue as you clearly have to have mutual agreement on costs, time frames, and other aspects.

It was a fascinating and thoroughly enjoyable trip and my thanks go to Czapek – and Xavier in particular. As a result I have a much better grasp of what actually goes into making a watch – particularly at the higher end. This, up to a point, also helps to justify the sometimes hefty prices one sees. So, I recommend that if you have the chance to do the same, simply grab it!

Words/Pictures: The Writer.

Note: The Writer did receive some complimentary meals/drinks but funded own flight/hotel.